Why Fine Tuning?

Most commercial users of deep learning models don’t train them from scratch. It’s demanding on hardware, requires a lot of input data, and takes a long time to train. The current trend forecasts an increase in this phenomenon in the future. The models keep getting larger, and not everyone will be able to afford their own “from scratch” solutions. Many companies already can’t.

Fortunately, they don’t have to. Taking an already trained model and adjusting it to a particular use case is much faster and budget-friendly. This common technique, called fine-tuning, allows us to leverage a relatively small dataset that would otherwise be insufficient to train a model from scratch. A short training on this specialized dataset is enough to nudge the model towards the desired behavior. It makes use of the vast knowledge the base model has already learned and only slightly modifies it. Because of this, fine-tuning is very effective on large, general-purpose models (i.e., large language models (LLMs)). They have a solid grasp of fundamentals and a wide array of knowledge already embedded into their weights. They provide a lot to “work with,” and, as such, fine-tuning becomes increasingly popular both in research and business alike.

LoRA Overview

There are several ways to fine-tune a model, each with its own set of limitations. Most concentrate on modifying only a small selection of weights, i.e., only the last layer of the model or the inserted so-called adaptive layers. This makes the fine-tuning easier but limits the learning capability.

In 2020, a new method was proposed and remains the golden standard as of 2024. Called Low Rank Adaptation (LoRA), it has become very popular due to its effectiveness, as well as memory and time efficiency. What’s unique about it is that it can be applied to an arbitrary portion of the model’s weights. You might imagine that this impressive learning flexibility comes with a heavy memory cost. After all, we can potentially modify many more weights in the model. It’s only logical that storing those modifications would be demanding, right?

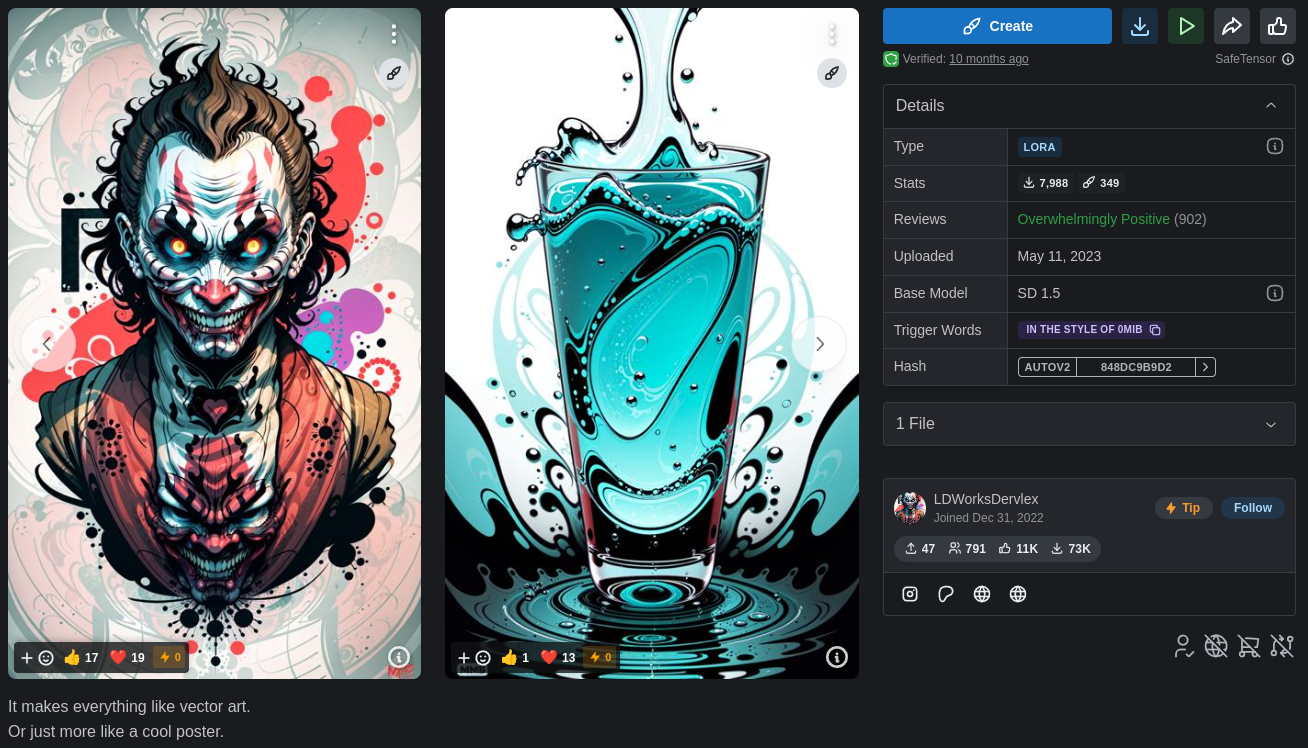

It turns out that no, it wouldn’t be as demanding as expected! The trick lies in the usage of low-rank matrices, which help reduce the necessary memory demand, which we will discuss in detail below. A nice feature of the LoRA method is its modularity. The changes in the weights resulting from fine-tuning can be stored in their own separate matrices and written to a lightweight file. Those can be easily shared with other users and applied to their base models. Experimenting with different LoRAs and even mix and matching them is thus very popular. So much so that sites like Civitai are literally flooded with spectacular LoRAs for image generation niche. Chances are that’s where you’ve first heard the term.

It’s worth pointing out though that LoRA is the current golden standard for fine-tuning in other deep learning fields as well, not just GenAI.

A completely random LoRA downloadable from Civitai: LoRA 0mib - Type of Vector Art

How Does It Work?

Relevant Papers

At the very core of what LoRA is stands a mathematical technique of low-rank representation of a matrix. Those two papers: 1) Paper 1 2) Paper 2

serve as an in-depth explanation of why the technique is relevant for machine learning. Here’s what the papers mean in simpler terms.

Low Intrinsic Dimension

The first one finds out that for deep learning models most of its knowledge (in other words, the patterns and relationships learned by them) can actually be explained by far fewer parameters than they contain. In fact, it turns out that the larger the model, the greater this effect is. Because those large models contain relatively few “core” parameters we are able to fine-tune them with small datasets in the first place. The core conclusion is this: when we want to fine-tune them, there are surprisingly few parameters that are really worth tweaking. In the paper they are referred to as an intrinsic dimension, as since there are so few of them, we’re saying that the models have a low intrinsic dimension.

Low-Rank Adaptation

Adaptation Matrix

The second paper goes a step further with this idea. Let’s say we want to fine-tune a matrix of weights of some model. Normally we would imagine the process as taking this matrix and iteratively changing its values in the fine-tuning training loop. And that’s true - but we can also think about this process in another way.

We can also imagine it as taking the original matrix of weights and, instead of manipulating its weights’ values in place, we can try adding to it a matrix of identical size. In this scenario, the original matrix would be unchanging. Instead, it would be the new matrix that is being fine-tuned (let’s call it an adaptation matrix). After adding it to the original, we would end up with the same changes in the weights’ values - but without touching the original matrix, which will prove beneficial later.

\[\text{W} = W_0 - \Delta W\]Where:

- W - is the fine-tuned set of weights

- W0 - is the original model’s set of weights

- ΔW - is a new set of weights, equal in size to W and W0, representing the incoming change in the model’s weights.

Low Rank Adaptation Matrix

The previous paragraph told us that we can separate our fine-tuning process into original matrix and an adaptation matrix that will contain all the changes. That’s interesting, but hardly what the second paper truly was about. Instead, it focused on the low-rank intrinsic dimension property of the models, as discovered in the first paper.

This property would also apply to our original matrix - W0, which is supposed to represent one of the layers of a large model. Let’s say it’s a 400 x 400 matrix. Out of its 160,000 parameters, only a fraction would be the core ones. But during fine-tuning described in the previous paragraph, we still created matrix ΔW of 160,000 parameters and tried to learn all of them, even though most didn’t really impact the performance of the model that much. The second paper says this - since only a fraction of W0 parameters are the core ones, why don’t we focus only on them during fine-tuning?

You could also formulate it as such: We should be able to learn a ΔW much smaller than 160,000 parameters and, after applying it to the original matrix, still achieve similar performance to a full-size adaptation matrix. This smaller matrix is often referred to as a low-rank matrix.

But before we do that, we need to answer two important questions:

1) What dimensions should our adaptation matrix be? The low-rank intrinsic dimension property of the model says that a fraction of its parameters should be enough to represent the patterns learned by the model. But how many parameters is that exactly? 400? 1000? We can’t just take a wild guess.

2) How do we add a smaller adaptation matrix to the original one? Just imagine that we’ve reduced the adaptation matrix to an arbitrary size of 20 x 20 because we think that we will have only 400 (20 * 20) core parameters. How do we add a 20 x 20 matrix to the original 400 x 400?

Singular Value Decomposition

Fortunately, there is a mathematical technique that lets us address the above two questions at once. Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) is a technique which I won’t discuss here in detail, but I’ll focus on the benefits it can provide us.

SVD takes in a matrix and returns three other matrices. Assuming our matrix in the shape rows x columns, they will have the following sizes:

- U - rows x rows - a matrix representing how each row is related to the others

- VT - columns x column - a matrix representing how each column is related to others

- Σ - rows x columns - a matrix of all zeroes except diagonal values. Those values represent how much variance is captured by their corresponding values in U and VT. U and VT are related to each other so one diagonal value in Σ has equivalents in both U and VT.

If we take a step back and consider what we’re getting out of this, then we’ll realize that our matrix Σ is a ranking of “importances” of features that we were after! With this, we can easily select an arbitrary number of top parameters for our core parameter selection. How many should we retain? That’s a hyperparameter in its own right - rank (r).

Based on the three matrices that we have, we can make an estimation for reasonable rank with energy retention or cumulative variance mathematical techniques. They will tell us what rank we have to pick so that our low-rank matrices still explain a desired percentage of variance (i.e., 90%).

Once we pick a reasonable rank, we no longer need our U, VT, or Σ. We already know what we were after. We know that matrices of sizes rows x rank (reduced U) and rank x columns (reduced VT) are enough to explain the amount of variance in the original matrix. So, this amount should be good enough for fine-tuning it too, right? That’s exactly the thesis of the 2021 paper pasted earlier.

Now we can answer the questions from the previous paragraph.

1) What dimensions should our adaptation matrix be? There should be two adaptation matrices. Rows x rank and columns x rank. We initialize them and will learn its parameters during fine-tuning.

2) How do we add a smaller adaptation matrix to the original one? Notice an interesting property of the two matrices mentioned above. When you multiply two low-rank adaptation matrices by each other, you’ll get a matrix of original size. And that’s how you can simply add the two together to introduce the fine-tuning changes to the original set of weights.

Those two low-rank adaptation matrices are smaller than the original weights. Fewer parameters mean easier and faster training and a lighter file to share with the community. The possibility of simply adding the loaded adaptation matrices onto the original model without the necessity to exchange the entirety of it adds a very convenient modularity aspect to the technique. And that’s why LoRA is so popular these days.

Sometimes you will also see an alpha hyperparameter in your LoRA pipeline. It’s a multiplication factor that gets applied to the adaptation matrix before it gets added to the original set of weights. It simply allows you to pick how big of an impact will the fine-tuning changes have on your original model.

An example of no LoRA applied vs alpha at strength: 4.0 and 12.0. Source for the image, as well as the banner: Civitai